In a house full of adult men of varying temperaments and origins, one can imagine that certain rules would be necessary to maintain peace and good order.

St. Dominic

by Fra Angelico

Saint Benedict, in fact, puts emphasis on this practical aspect when regulating the silence which the monks must keep at night: it is intended to allow all to sleep without being kept up by the importunity of those who would want to talk. This silence of the night, then, takes on a grave character colored by fraternal charity. This silence of the night or great silence is normally the one that captures the popular mind, with images of monks in dark corridors using sign language to communicate about secret things.

Nonetheless, this was not the universal practice of ancient monasticism. We read in the Conferences of Cassian that he and his friend Germanus often were up until the late hours of the night listening to the wisdom of the elders in the desert of Egypt. This desert tradition valued much the long night vigils and watches that are frequent in Eastern Christian monasticism. But these late-night vigils and conferences made much more sense in a hot desert climate like that of Egypt or Palestine. The days were scorching and one could not get out much in the sun or work. The night was the time when it was cool and one could move about and work and pray and meet, unhindered by the heat of the sun.

It could seem from these historical aspects that monastic silence is simply a question of practical import, but this would be a false conclusion…

While certainly full of practical considerations, the Holy Rule also looks to the moral formation of the monks. Citing the book of Proverbs (10:19), it claims that “In much speaking, you cannot avoid sin”, and even that “Death and life are in the power of the tongue” (18:21). Far from just monastic wisdom, these passages from the old Testament remind us that man’s life is a constant temptation. When we speak, we risk so many things: detraction, slander, lies, complaining, vanity, pride, and much more. Not that speech is inherently evil: it is a gift of God that corresponds to our intelligent and social nature. But the reality of sin brought constant temptation to us even in this most important of our rational capacities.

When placed next to this aspect of sin, silence takes on a much greater role. The Rule does not obsess with particulars about the night and sleep, but does lay down rules about speaking which pertain to the whole day, even to the monks whole life (Holy Rule, chp. VI). Speaking is rare, it is limited. The monk is to be concise and to the point, without superfluity. Such can be a challenge for the new monk, but it opens a door to more important conversations.

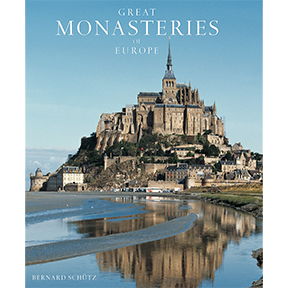

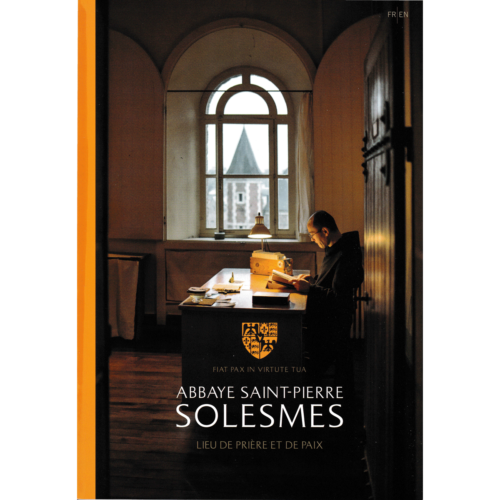

Indeed, this silence of the mind and of the heart is the privileged place of encounter with God. The quiet order of a monastery provides an image of this externally, to the monk and to those outside. But mere lack of speaking is not enough; one needs an internal silence that makes room for God to speak to us. This is the silence of the true monk and the saint. It has nothing to do with being anti-social or taciturn, it is to be present to God, and also to one’s neighbor.

In the modern world we are all plagued by noise and social contact of an inferior sort as mitigated by technology. Sometimes speaking in the physical presence of another would be a great improvement on an unending stream of emails and texts and social networking. One certainly needs time away from these with real human contact, but one needs even more that time of silence. If we are ever to have that interior peace where God can come and be near to us, we have to find at least at certain times for this exterior quiet. It brings the monk much strength and balance, and we hope that you can share it with us too, whether at the monastery or in your own lives.