Dear Friend of Clear Creek Abbey,

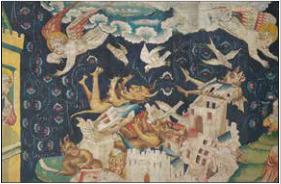

After repeated threats, in the year 410 “the Visigoths appeared outside Rome in force and the senate prepared to resist, but in the middle of the night rebellious slaves opened the Salarian Gate to the attackers, who poured in and set fire to the nearby houses. ‘Eleven hundred and sixty three years after the foundation of Rome,’ Gibbon pronounced, ‘the Imperial city, which had subdued and civilized so considerable a part of mankind, was delivered to the licentious fury of the tribes of Germany and Scythia’” (Richard Cavendish, “The Visigoths sack Rome”, History Today). The Romans were left in a state of despair, and many of them blamed the Christians for this unmitigated disaster.

It was Saint Augustine who set himself the task of refuting the charge and restoring hope to the Christians.  On the City of God against the Pagans, or simply The City of God, was his response. Not only did the work address the problem of Divine Providence with respect to the Empire, but he climbed to a height unequaled, no doubt, by historians before him. In the words of a French writer, “In a flash of genius which transformed the apology into a philosophy of history, he saw in one glance the destinies of the world grouped around the Christian religion, the one and only religion, which properly understood, is seen to go back to the beginnings and which leads mankind to its final end” (E. Portalié, cited in F. Cayré, Manual of Patrology).

On the City of God against the Pagans, or simply The City of God, was his response. Not only did the work address the problem of Divine Providence with respect to the Empire, but he climbed to a height unequaled, no doubt, by historians before him. In the words of a French writer, “In a flash of genius which transformed the apology into a philosophy of history, he saw in one glance the destinies of the world grouped around the Christian religion, the one and only religion, which properly understood, is seen to go back to the beginnings and which leads mankind to its final end” (E. Portalié, cited in F. Cayré, Manual of Patrology).

Saint Augustine did not seek to restore the Roman Empire, but rather to direct mankind’s gaze toward a better city, one beyond the assaults of time. And this he did. However, as the history of the world was not destined to end with the Roman Empire, out of the ashes of Rome and the shadows that followed something else emerged, something unexpected, something surprising in its scope, something quite wonderful all in all, something which would come to be called “Christendom.” That is a whole story in itself that needs to be retold.

Many Americans are saddened these days by what is the rather obvious decline of our nation. We are terribly divided in our political views; while the economy is booming for the wealthy, good jobs for the average citizen are becoming scarce; the family as the basic building block of society is in great trouble. Then, of course, there is the global health crisis that has hurt us too in many ways. Where, as Christians, do we go from here? Are we not in need of another Augustine and of another City of God to lift up our souls?

No doubt God will send us such a Saint, but in the meantime we are not without resources. One of the great factors that brought about the Christian era following the decline of the Roman Empire was a little book of much less grandeur than The City of God, but no less precious. It was the Rule for monks written by Saint Benedict. Unlike most practical literary works, the Rule has weathered already fifteen centuries and is still with us. Today, as in the sixth century, we find in these pages a guide for human life, directly applicable to monks and usefully, though not directly, applicable to the life of any man or woman who might open it.

The challenge of finding our way back to a way of life in harmony with our Catholic Christian faith has also been helped in recent decades by the more prescient minds, who saw the shipwreck coming. One effort has been to encourage us to get closer to the land, together with an economy based on the small farm, the small store, and, in a word, what is local. The distributist movement, founded by Hilaire Belloc and his friends, developed a language and a doctrine that pointed in this direction, as did the book written by E. F. Schumacher, Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. The Catholic Church had already incorporated such considerations into its social doctrine, beginning with the encyclical Rerum Novarum, one source of inspiration for the early distributists. Various papal teachings on the matter have followed that first encyclical of Pope Leo XIII up until the present time. The Holy Father, Pope  Francis says this: “The solution is not an openness that spurns its own richness. Just as there can be no dialogue with “others” without a sense of our own identity, so there can be no openness between peoples except on the basis of love for one’s own land, one’s own people, one’s own cultural roots. … We need to sink our roots deeper into the fertile soil and history of our native place, which is a gift of God. We can work on a small scale, in our own neighborhood, but with a larger perspective” (Encyclical Letter Fratelli Tutti, nn. 143, 145).

Francis says this: “The solution is not an openness that spurns its own richness. Just as there can be no dialogue with “others” without a sense of our own identity, so there can be no openness between peoples except on the basis of love for one’s own land, one’s own people, one’s own cultural roots. … We need to sink our roots deeper into the fertile soil and history of our native place, which is a gift of God. We can work on a small scale, in our own neighborhood, but with a larger perspective” (Encyclical Letter Fratelli Tutti, nn. 143, 145).

The choice becomes even clearer in our day between a monstrous globalism on the one hand, and a more human “localism” on the other. Will we continue to follow the moguls of multi-national capitalism and the wizards of the social media or the Poverello of Assisi, Saint Benedict, and G. K. Chesterton?

More pointedly, what will bring us to a concrete—one might say an existential—solution for the foreseeable future? “Time will tell,” they say. We monks, in any case, in our hidden corner of Christendom (or what’s left of it), will do what we can. We shall continue to build our abbey, and we hope the local community that surrounds us, our village, will likewise blossom for the glory of God. Perhaps monastery and village—someday—will even lead to the establishment of a city (the village cannot stand by itself): not the sad city of the Antichrist (Heaven forbid!), but rather a certain earthly foreshadowing of the City of God, the true Catholic City.

br. Philip Anderson, abbot