Dear Friend of Clear Creek Abbey,

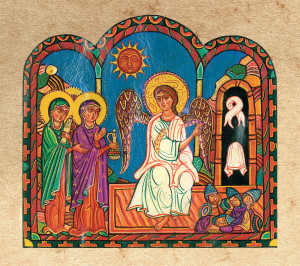

To the Christian who has run the race, who has reached the Sacred Triduum in prayer and fasting, the light of Easter morning brings the unwavering certitude of a victory achieved, truly the end of “the war to end all wars.” It speaks of a peace that, at long last, does not disappoint us. The symbol of this solid victory is the heavy stone that was rolled away from the entrance to Christ’s tomb by an angel after an earthquake. This was no ordinary angel but a spirit whose countenance was as lightning, whose clothes were white as snow, one who made the Roman guards freeze with terror. He sits peacefully on the stone.

As for the man or woman of our day who has missed this religious cataclysm we call Easter (a most unusual and beneficial cataclysm), there is more probably the uneasy feeling of a world in turmoil, an uneasiness fed by the dire predictions of economists and

So what does the Angel of the Resurrection contemplate from his special vantage point atop the great stone? We cannot divine his thoughts regarding the majesty of God, but with regard to the things of earth he must gaze in angelic amazement at the comings and goings of these poor followers of the Lord, struggling to come to grips with the reality of Christ’s rising from the dead.

As was true during the darkest hours of Good Friday, it is the women who are the most courageous on Easter morning. They brave both the shadows of the night and the threat of the Roman guards—not to mention the huge stone. However, once they have summed up the situation, they run to the Apostles—to the men. It was, after all, in keeping with God’s infinite wisdom, upon men that the authority of the priesthood was bestowed. It was these same men who received ordination; it was their feet Jesus washed in the Upper Room on Holy Thursday. The holy women need the steadiness of men at this important hour. And it will be there. Saint Peter, the “Rock,” finally emerges from his sorrow as the news of Easter breaks, and rises to the occasion, even though it will take the grace of Pentecost to fill him with evangelical fortitude. “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” But in these early hours of Easter morning, both men and women are in something of a panic. Only little by little will they realize the immense implications of that rock rolled away from the mouth of the sepulcher. For the moment they are filled with fear.

In fact, there is a great deal of running taking place. Saint Mary Magdalen runs to inform the Apostles about the rolled stone. Then the other holy women, who encounter two angels inside the tomb, run to tell the rest of the disciples. Saint Peter and Saint John, upon learning the great news, engage in a famous footrace to the place of the Resurrection. It is all very human but also heavy with theological meaning: everyone is running toward the steadiness of Christ who, even more than Peter, is the Rock, the stone which the builders rejected, the Cornerstone. Truly, the supernatural has dawned on the earth this day as never before.

Only our living faith can begin to evaluate and situate this story of Christ’s rising from the dead, a story that could never be captured by the cameras and recording equipment of our modern journalists. There is something here infinitely more profound than the latest “scoop.” And so it is that the sacred peace of the holy liturgy of Easter, awash in the supernatural light of faith, can and must save us from the chaos of a world drunk with sound bites and images. The great stone that was rolled away from the Empty Tomb, but which then stood steady, gives us the image of Divine Peace attained for us through Christ’s Passion and Death.

In the end it is all so simple. “Peace I leave you,” says the Lord, “my peace I give unto you: not asPrint Version the world giveth, do I give unto you. Let not your heart be troubled . . .” Jesus is forever the Risen One, He is the Rock, He is the King of Divine Mercy.

+ br. Philip Anderson, abbot

Dear Friend of Clear Creek Abbey,

To the Christian who has run the race, who has reached the Sacred Triduum in prayer and fasting, the light of Easter morning brings the unwavering certitude of a victory achieved, truly the end of “the war to end all wars.” It speaks of a peace that, at long last, does not disappoint us. The symbol of this solid victory is the heavy stone that was rolled away from the entrance to Christ’s tomb by an angel after an earthquake. This was no ordinary angel but a spirit whose countenance was as lightning, whose clothes were white as snow, one who made the Roman guards freeze with terror. He sits peacefully on the stone.

As for the man or woman of our day who has missed this religious cataclysm we call Easter (a most unusual and beneficial cataclysm), there is more probably the uneasy feeling of a world in turmoil, an uneasiness fed by the dire predictions of economists and

So what does the Angel of the Resurrection contemplate from his special vantage point atop the great stone? We cannot divine his thoughts regarding the majesty of God, but with regard to the things of earth he must gaze in angelic amazement at the comings and goings of these poor followers of the Lord, struggling to come to grips with the reality of Christ’s rising from the dead.

As was true during the darkest hours of Good Friday, it is the women who are the most courageous on Easter morning. They brave both the shadows of the night and the threat of the Roman guards—not to mention the huge stone. However, once they have summed up the situation, they run to the Apostles—to the men. It was, after all, in keeping with God’s infinite wisdom, upon men that the authority of the priesthood was bestowed. It was these same men who received ordination; it was their feet Jesus washed in the Upper Room on Holy Thursday. The holy women need the steadiness of men at this important hour. And it will be there. Saint Peter, the “Rock,” finally emerges from his sorrow as the news of Easter breaks, and rises to the occasion, even though it will take the grace of Pentecost to fill him with evangelical fortitude. “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” But in these early hours of Easter morning, both men and women are in something of a panic. Only little by little will they realize the immense implications of that rock rolled away from the mouth of the sepulcher. For the moment they are filled with fear.

In fact, there is a great deal of running taking place. Saint Mary Magdalen runs to inform the Apostles about the rolled stone. Then the other holy women, who encounter two angels inside the tomb, run to tell the rest of the disciples. Saint Peter and Saint John, upon learning the great news, engage in a famous footrace to the place of the Resurrection. It is all very human but also heavy with theological meaning: everyone is running toward the steadiness of Christ who, even more than Peter, is the Rock, the stone which the builders rejected, the Cornerstone. Truly, the supernatural has dawned on the earth this day as never before.

Only our living faith can begin to evaluate and situate this story of Christ’s rising from the dead, a story that could never be captured by the cameras and recording equipment of our modern journalists. There is something here infinitely more profound than the latest “scoop.” And so it is that the sacred peace of the holy liturgy of Easter, awash in the supernatural light of faith, can and must save us from the chaos of a world drunk with sound bites and images. The great stone that was rolled away from the Empty Tomb, but which then stood steady, gives us the image of Divine Peace attained for us through Christ’s Passion and Death.

In the end it is all so simple. “Peace I leave you,” says the Lord, “my peace I give unto you: not asPrint Version the world giveth, do I give unto you. Let not your heart be troubled . . .” Jesus is forever the Risen One, He is the Rock, He is the King of Divine Mercy.

+ br. Philip Anderson, abbot